Sharks have been skulking around the world’s oceans for about 420 million years, predating dinosaurs by 189 million years. Sharks first emerged during the “Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event” of the Paleozoic era, according to paleontologists who study the fossilized shark teeth long buried in land that used to be the floors of prehistoric oceans.

From these fossils, scientists have been able to learn a great deal of information about prehistoric sharks, including a good idea about what they looked like, what they ate, and how long certain species survived. Perhaps the most interesting fact of all about sharks is that they survived all five of the major mass extinctions that have occurred since the emergence of life on earth.

The Age of Fishes

During the Devonian period (408 to 360 million years ago,) known as “The Age of Fishes,” sharks looked much different than they do today. They were much more fishlike in shape, and they were considerably smaller than our modern-day sharks.

One shark from this time period, Cladoselaches, measured about four feet in length and had a torpedo-shaped body. Strangely absent from this species were the placoid scales that cover the skin of most sharks, both ancient and modern. But even stranger is the absence of claspers, which male sharks use to deliver sperm to the female. It’s not known exactly how Cladoselaches reproduced without this essential sperm delivery device, but it’s obvious that they did, because they remained in the oceans for 100 million years before they became extinct.

The Golden Age of Sharks

A mass extinction at the end of the Devonian period gave birth to the Carboniferous period, which is dubbed “The Golden Age of Sharks” due to the extinction of the shark’s top predators, which put the sharks on top of the food chain. This period saw the all-time highest diversification of shark species in 45 different taxonomic families.

Two sharks from the Carboniferous period stand out for their particularly bizarre appearance.

Male Stethacanthus Sharks sported a dorsal fin that resembled an anvil. It was flat on top and covered in scales. The top of its head was also flat and completely covered in small spikes, which may have been used for defense or to attract a mate.

Helicoprion Sharks, also known as “whorl-toothed” sharks, featured a lower jaw that jutted out with its teeth arranged in a circle, appearing as if a circular saw or pizza cutter blade was attached to it.

The End of the Golden Age

Around 250 million years ago, near the end of the Permian period, what was likely an abrupt change in the climate resulted in the mass extinction of over 90 percent of all marine species. This event is known as the Great Dying. Sharks barely survived this extinction, and scientists believe that they did so by taking refuge in deeper waters.

The Cladodontomorph Shark, which emerged 100 million years before this extinction event, was thought to be one of the many shark species to meet its end during the Great Dying, but scientists recently uncovered fossils of this shallow-water shark that date back to about 133 million years ago, proving that they actually survived the extinction. Based on where the fossils were found, it appears that Cladodontomorph moved to waters over 650 feet deep.

Another shark that survived the Great Dying was the Orthacanthus Shark, a 10-foot long creature that appeared to be mostly comprised of a head and which featured formidable, double-fanged teeth lining the jaw.

A New Beginning

The Great Dying ushered in the Mesozoic Era. During the Triassic period, which is when the dinosaurs finally showed up, sharks began to slowly recover in number and continued to diversify, despite the emergence of the Great marine reptiles, who became the new rulers of the world’s oceans. By the end of the Jurassic period, all of the eight extant shark orders that we know today had appeared.

At the close of the Mesozoic Era, during the Cretaceous period, another mass extinction wiped out the dinosaurs and most of the Great marine reptiles, which put the sharks back at the top of the marine food chain and ready to thrive in the new era.

All Hail Megalodon!

The Cenozoic Era has been very good to sharks. Mammals like whales, dolphins, and seals took to the oceans and have provided a delicious and nutritious food source for the sharks ever since. More food meant bigger sharks, and during the Tertiary period, they grew larger and took on their modern-day characteristics.

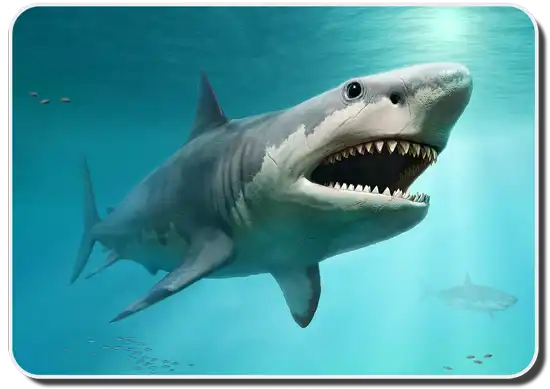

The late Ogligocene epoch saw the emergence of the most fearsome shark that has ever lived and the largest predatory marine animal the planet has ever seen. Megalodon was named for its enormous teeth, which grew to seven inches long. Only T-Rex’s teeth were bigger than Megalodon’s.

Megalodon had the most powerful bite of any creature, ever. Whereas a lion bites down with 500 pounds of force and a Great White Shark with 1.8 tons of force, Megalodon’s bite came with 18.2 tons of force. A single, casual bite from this massive shark could crush the skull of a giant prehistoric whale as easily as if it were a chocolate truffle.

Reaching a length of over 60 feet long and a weight of 100 tons, Megalodon thrived for over 30 million years as the undisputed king of the seas, until it suddenly became extinct at the end of the Pliocene epoch. No one is really sure why this gigantic creature died out, but theories include the disappearance of giant whales, its favorite snack, and global cooling, which led to the remaining shark species adapting to different water temperatures, enabling them to spread across the oceans.

Modern Day Sharks

Today sharks live all over the world, from warm equatorial waters to the icy cold depths surrounding Greenland. Although they still thrive and continue to maintain their position high up on the marine food chain, a comparatively young and highly destructive species known as Homo sapiens may end up being the demise of many ancient shark species.

Scientists have recently increased original estimates of the number of sharks killed by humans each year from 73 million to 100 million. They stress that this number is a low estimate, and the real number may be as high as 273 million sharks meeting their demise at the hands of fisherman, sportsmen, and the degradation of ocean ecosystems due to drilling for oil, increasing pollution, and other unsavory human activities.